- Home

- Play & Learn Home

- Online Enrichment

- Experience Modern Israel

- Israel It's Complicated

- Jewish and Me

- Jewish Holidays Jewish Values

- Jewish Values in Genesis and Jewish Values in Exodus

- Min Ha’aretz

- Our Place in the Universe

- Simply Seder

- The Prophets: Speaking Out for Justice

- Making T'filah Meaningful

- Make, Create, Celebrate

- Yom Haatzmaut Resources

- Hebrew Apps

- About The OLC

- What is the OLC?

- Introduction

- Get Started

- Resources

- OLC Content

- Parent Materials

- See My OLC Classes

- Store

Hebrew with Intent: A School’s Culture Transformed

Written by Behrman House Staff, 18 of November, 2015

In the Spotlight: Washington Hebrew Congregation, Washington, D.C.

Hebrew is unquestionably a significant piece of what it means to be Jewish. This is the third in a series about educators and their experiences developing a clear-eyed purpose for Hebrew in their schools and a program that supports those goals.

At Washington Hebrew Congregation—one of the oldest and largest Reform congregations in the U.S.— students ask their peers for help and kids engage with clergy face to face. The school culture there has changed, because of Hebrew.

The school has long based its Hebrew curriculum on liturgy to ensure that its 900 students have the ability, skills and confidence to participate in any worship experience in the world. “Whether it’s during a kiddush or a wedding or a Passover seder, we want our students to feel comfortable and have any opportunity to use sacred language in a spiritual context. That’s why we teach Hebrew,” says Stephanie Tankel, director of Washington Hebrew’s religious school.

The school has long based its Hebrew curriculum on liturgy to ensure that its 900 students have the ability, skills and confidence to participate in any worship experience in the world. “Whether it’s during a kiddush or a wedding or a Passover seder, we want our students to feel comfortable and have any opportunity to use sacred language in a spiritual context. That’s why we teach Hebrew,” says Stephanie Tankel, director of Washington Hebrew’s religious school.

Guided by that goal, a few years ago the school took a fresh look at its Hebrew program and chose to start language instruction earlier, now beginning in third grade using Alef Bet Quest. But educators there also recognized that “there’s no such thing as one size fits all, especially with a school our size,” Tankel says. She and her team found that students had many different learning styles and abilities and schedules, and some fell behind if they missed a class or came in late.

They turned to the Mitkadem curriculum, a self-paced learning program focused on prayer and synagogue skills, so students could move at their own speed. They phased it in over several years, with a lot of teacher training. “It came from this notion that kids could move at their own pace, but for us, it’s become apparent that there’s much more than that,” according to Tankel.

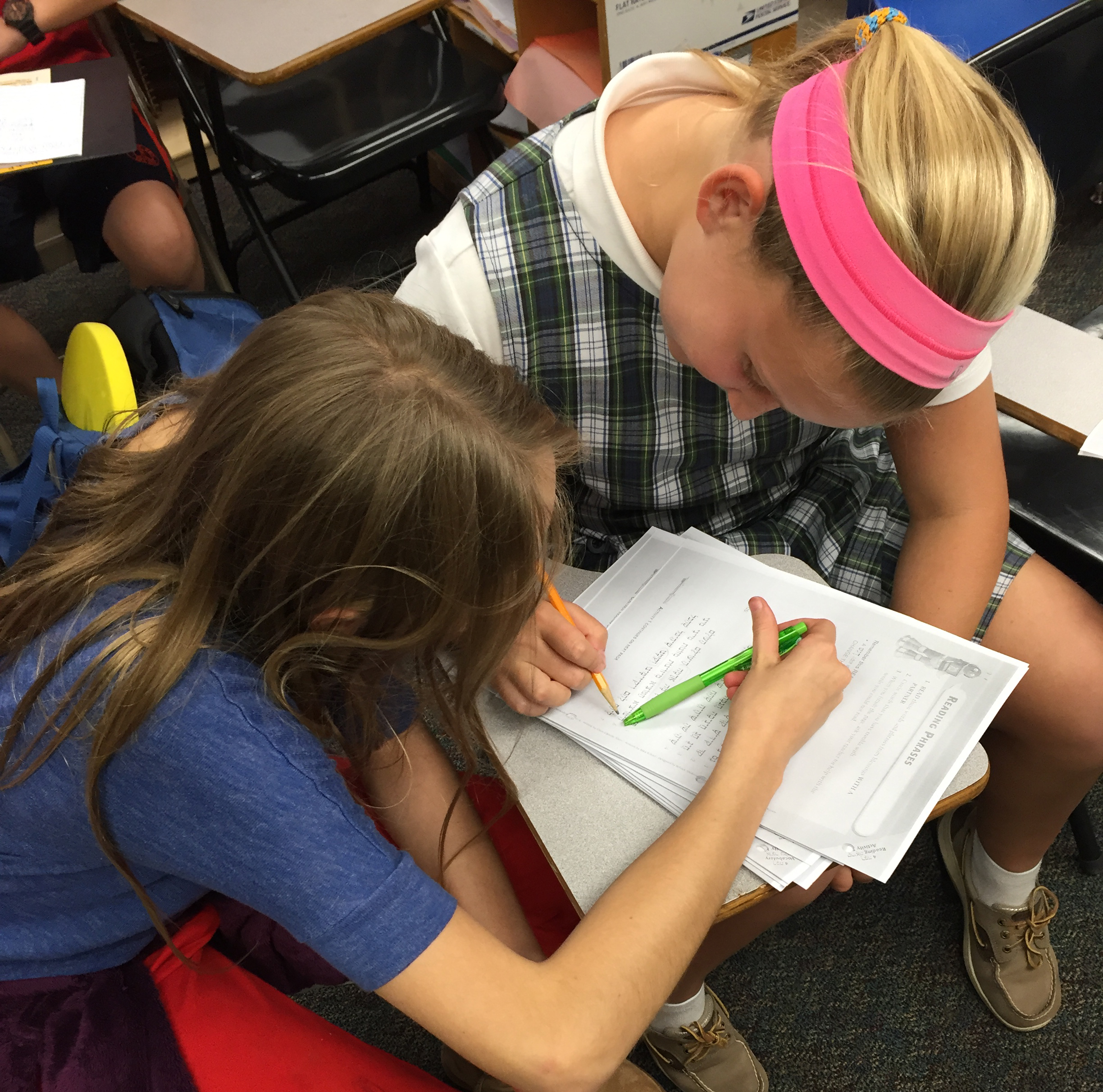

Washington Hebrew educators want the experience of Hebrew learning to be “empowering,” and the personalized curriculum allows students to, in their own way, control their learning. The Mitkadem curriculum is organized into 23 levels, and each one contains multiple types of activities focused around grammar, vocabulary and reading. Students who prefer to work alone can do so, while others might be more interested in practicing reading with a partner. “No one is looking over their shoulder, and everyone is working on their own page,” Tankel says. “So there’s no sense of shame or judgement. Everyone knows they have their own charted journey. Student-led learning gives kids a reason to feel they belong.”

“This approach has completely changed the culture of our school,” she says. “Kids are more likely now to talk to one another. It’s not about sitting next to your friend, but asking another student about a particular section you don’t understand. It encourages talk to peers, and not just talking to teachers to ask a question.”

Not only does each child have their own learning experience, but students at Washington Hebrew are assessed on their Hebrew skills in a personalized way. Students must pass both an oral and written test to successfully complete a level and advance to the next. At Washington Hebrew, not only do students have to read to their teachers, but they also have to read to either Tankel or a clergy member or another lead educator.

“This means we know where every single child is. It’s a system of checks and balances so kids don’t fall through the cracks,” she says. Tankel keeps an excel file documenting who heard the child read and when.

“With a school this large, it’s changed our culture to have kids read to clergy and leadership. It teaches children that in the larger world they have to advocate for themselves,” Tankel says. “Little by little, the kids are learning to approach us and say, ‘My teacher says I’m ready to read to you,’ or ‘I’m going to read, but I’m going to do it slowly,’ or ‘I want to give it a try.’ It’s the effort that matters. Kids aren’t just learning Hebrew but it’s an opportunity to build community and learn how engage clergy.”

Teachers too, have benefitted from the Hebrew program. Intended to engage students with vastly different learning styles, using Mitkadem in the religious school has also changed teaching methods in significant ways. There isn’t as much pressure on teachers to keep all the students on one level, and teachers have learned more skills like motivation and creating incentives, which is challenging to manage. The school also learned that it needed assistant teachers, typically college students, in every class, in a way they hadn’t needed them before.

“The classroom is loud now. It’s buzzing because kids are learning individually or in small groups or clusters,” Tankel says. “A side benefit to the way we teach Hebrew is that if a student comes in late, they grab their materials and it doesn’t feel like they’re interrupting or disrupting. It’s been a huge benefit to the teachers and the class flow.”

Grown from its objective to teach liturgical Hebrew in an educationally sound yet flexible program, Washington Hebrew has transformed its school culture into one of pride, personal responsibility, and engagement across traditional boundaries. For years, the school has conducted annual end-of-year surveys of both students and parents, and for years both groups always reported liking the art projects and Judaics the best. Now, the Hebrew curriculum tops the list.