- Home

- Play & Learn Home

- Online Enrichment

- Experience Modern Israel

- Israel It's Complicated

- Jewish and Me

- Jewish Holidays Jewish Values

- Jewish Values in Genesis and Jewish Values in Exodus

- Min Ha’aretz

- Our Place in the Universe

- Simply Seder

- The Prophets: Speaking Out for Justice

- Making T'filah Meaningful

- Make, Create, Celebrate

- Yom Haatzmaut Resources

- Hebrew Apps

- About The OLC

- What is the OLC?

- Introduction

- Get Started

- Resources

- OLC Content

- Parent Materials

- See My OLC Classes

- Store

Behrman House Blog

Fear and Loathing and Assessment

Written by Vicki Weber, RJE, 20 of June, 2016

“May I offer you some feedback?”

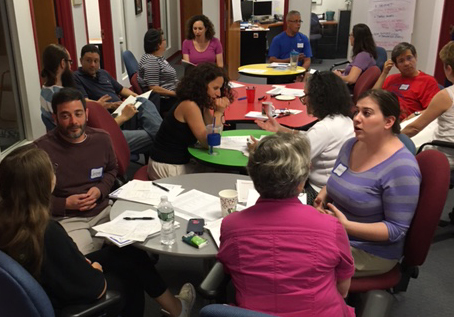

More nerve-wracking words are rarely spoken or heard in the workplace. We discuss student assessment regularly, but we often avoid it with colleagues and staff. Let’s face it, we loathe those conversations. At a recent in-service learning day at Behrman House (photo at right) we offered up our feelings about assessments: They make us squirm. And the only thing we fear more than getting an assessment is having to give one.

So we find reasons to avoid it. “I feel unqualified;” “I don’t want to hurt any feelings;” “I’m concerned about damaging our relationship.” And yet, assessment is not only the best way to let our colleagues and our staff members know how they can improve their work, it’s also the best way to learn about how we ourselves can do better. Without assessment, we can’t make change. We’re stuck. Worse, we may even do damage.

How do we remain true to our empathetic selves and also offer clear-eyed assessments in our schools and organizations? How do we develop an assessment practice that we and our colleagues are willing to actually do? Just as in many areas of education, we can be helped here by using protocols. Here are three ideas:

1. At Behrman House, in addition to periodically facing down our fear and loathing of assessment, we also regularly practice a protocol called "Plus/Delta." At the end of a meeting or project or event (or even at the end of our in-service learning day!) we gather for about five minutes to note what worked well enough that we want to be sure to do again (that’s Plus), and what things we want to do differently (that’s Delta, the triangular mathematical symbol for change, named for the Greek letter).

The visual organizer for this activity is a flip chart with a line drawn vertically down the center, plusses on the left, deltas on the right. The key to this protocol is to gather input from everyone involved, and to consistently phrase the items as either things to do again or things to do differently. (NOT things to avoid or things that ‘went wrong’). It’s best if the organizer of the project is the note taker for this, listening to and recording the observations, and without answering back in the moment. All the recorded observations are typed up and used to plan future events, meetings, and engagements.

2. Another approach we are beginning to implement is for one-on-one conversations, and comes courtesy of Dr. Michael Zeldin, outgoing Senior National Director of HUC-JIR’s Schools of Education. It employs a gracious and gentle vocabulary -- “I appreciate, I notice, I wonder” -- to help us enter into conversations and then encourage us to dig deeper, focusing on both supporting and challenging a colleague.

3. And just the other evening, my younger son was telling us about the feedback protocol used in his computer programming course. After their daily work with a partner on a programming problem, each partner is encouraged to offer the other an assessment they call ASK: Actionable, Specific, and Kind. By developing this daily practice, the students are helping each other become both stronger programmers and more effective collaborators, and are losing their fear of telling one another what’s important.

We know how useful good protocols are in eliciting memorable learning moments. As it turns out, they can also help us develop essential regular practices to support and challenge our colleagues, ourselves, and our organizations and achieve real change by overcoming our fear of authentic assessment.